Variety is the spice of life. If everything were the same it would be rather boring. Happily, there is natural variety in everything.

Variety is the spice of life. If everything were the same it would be rather boring. Happily, there is natural variety in everything.

Let me use an example to explain:

I was thinking about this as I was walking the dog the other day. I use the same route, along the beach each day, and it takes me roughly the same time – about 30 minutes.

If I actually timed myself each and every day (and didn’t let this fact change my behaviour) then I would find that the walk might take me on average 30 minutes but it could range anywhere between, say, 26 and 37 minutes.

I think you would agree with me that it would be somewhat bizarre if it always took me, say, exactly 29 minutes and 41 seconds to walk the dog – that would just be weird!

You understand that there are all sorts of reasons as to why the time would vary slightly, such as:

- how I am feeling (was it a late night last night?);

- what the weather is doing, whether the tide is up or down, and even perhaps what season it is;

- who I meet on the way and their desired level of interaction (i.e. they have some juicy gossip vs. they are in a hurry);

- what the dog is interested in sniffing…which (I presume) depends on what other dogs have been passed recently;

- if the dog needs to ‘down load’ or not and, if so, how long this will take today!

- …and so on.

There are, likely, many thousands of little reasons that would cause variation. None of these have anything special about them – they are just the variables that exist within that process, the majority of which I have little or no control over.

Now, I might have timed myself as taking 30 mins. and 20 seconds yesterday, but taken only 29 mins. and 12 seconds today. Is this better? Have I improved? Against what purpose?

Here’s 3 weeks of imaginary dog walking data in a control chart:

A few things to note:

- You can now easily see the variation within and that it took between 26 and 37 minutes and, on average, 30 mins. Understanding of this variation is hidden until you visualise it;

- The red lines refer to upper and lower control limits: they are mathematically worked out from the data…you don’t need to worry about how but they signify the range within the data. The important bit is that all of the times sit within these two red lines and this shows that my dog walking is ‘in control’ (stable) and therefore the time range that it will take tomorrow can be predicted with a high degree of confidence!*

- If a particular walk had taken a time that sits outside of the two red lines, then I can say with a high degree of confidence that something ‘special’ happened – perhaps the dog had a limp, or I met up with a long lost friend or…..

- Any movement within the two red lines is likely to just be noise and, as such, I shouldn’t be surprised about it at all. Anything outside of the red lines is what we would call a signal, in that it is likely that something quite different occurred.

* This is actually quite profound. It’s worth considering that I cannot predict if I just have a binary comparison (two pieces of data). Knowing that it took 30 mins 20 secs. yesterday and 29 mins 12 secs. today is what is referred to as driving by looking in the rear view mirror. It doesn’t help me look forward.

Back to the world of work

The above example can equally be applied to all our processes at work…yet we ignore this reality. In fact, worse than ignoring it, we act like this isn’t so! We seem to love making binary comparisons (e.g. this week vs. last week), deriving a supposed reason for the difference and then:

- congratulating people for ‘improvements’; or

- chastising people for ‘slipping backwards’ whilst coming up with supposed solutions to do something about it (which is in actual fact merely tampering)

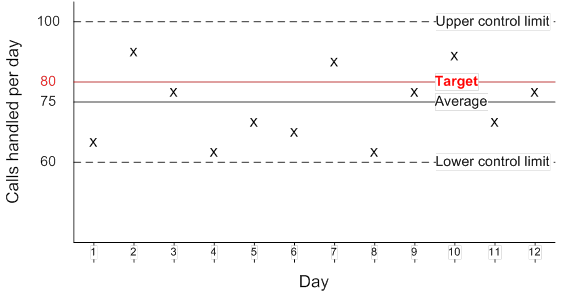

So, hopefully you are happy with my walking the dog scenario….here’s a work-related example:

- Bob, Jim and Jane have each been tasked with handling incoming calls*. They have each been given a daily target of handling 80 calls a day as a motivator!

(* you can substitute any sort of activity here instead of handling calls: such as sell something, make something, perform something….)

- In reality there is so much about a call that the ‘call agent’ cannot control. Using Professor Frances Frei’s 5 types of service demand variation, we can see the following:

- Arrival variability: when/ whether calls come in. If no calls are coming in at a point in time, the call agent can’t handle one!

- Request variability: what the customer is asking for. This could be simple or complex to properly handle

- Capability variability: how much the customer understands. Are they knowledgeable about their need or do they need a great deal explaining?

- Effort variability: how much help the customer wants. Are they happy to do things for themselves, or do they want the call agent to do it all for them?

- Subjective preference variability: different customers have different opinions on things e.g. are they happy just to accept the price or are they price sensitive and want the call agent to break it down into all its parts and explain the rationale for each?

Now, the above could cause a huge difference in call length and hence how many calls can be handled…but there’s not a great deal about the above that Bob, Jim and Jane can do much about – and nor should they try to!. It is pure chance (a lottery) as to which calls they are asked to handle.

As a result, we can expect natural variation as to the number of calls they can handle in a given day. If we were to plot it on a control chart we might see something very similar to the dog walking control chart….something like this:

We can see that:

- the process appears to be under control and that, assuming we don’t change the system, the predictable range of calls that a call agent can handle in a day is between 60 and 100;

- it would be daft to congratulate, say, Bob one day for achieving 95 and then chastise him the next for ‘only’ achieving 77…yet this is what we usually do!

Targets are worse than useless

Let’s go back to that (motivational?!) target of 80 calls a day. From the diagram we can see that:

- if I set the target at 60 or below then the call agents can almost guarantee that they will achieve it every day;

- conversely, if I set the target at 100 or above, they will virtually never be able to achieve it;

- finally, if I set the target anywhere between 60 or 100, it becomes a daily lottery as to whether they will achieve it or not.

….but, without this knowledge, we think that targets are doing important things.

What they actually do is cause our process performers to do things which go against the purpose of the system. I’ve written about the things people understandably do in an earlier post titled The trouble with targets.

What should we actually want?

We shouldn’t be pressuring our call agents (or any of our process performers) to achieve a target for each individual unit (or for an average of a group of units). We should be considering how we can change the system itself (e.g. the process) so that we shift and/or tighten the range of what it can achieve.

So, hopefully you now have an understanding of:

- variation: that it is a natural occurrence…which we would do well to understand;

- binary comparisons and that these can’t help us predict;

- targets and why they are worse than useless; and

- system, and why we should be trying to improve its capability (i.e. for all units going through it), rather than trying to force individual units through it quicker.

Once we understand the variation within our system we now have a useful measure (NOT target) to consider what our system is capable of, why this variation exists and whether any changes we make are in fact improvements.

Going back to Purpose

You might say to me “but Steve, you could set a target for your dog walks, say 30 mins, and you could do things to make it!”

I would say that, yes, I could and it would change my behaviours…but the crucial point is this: What is the purpose of the dog walk?

- It isn’t to get it done in a certain time

- It’s about me and the dog getting what we need out of it!

The same comparison can be said for a customer call: Our purpose should be to properly and fully assist that particular customer, not meet a target. We should expect much failure demand and rework to be created from behaviours caused by targets.

Do you understand the variation within your processes? Do you rely on binary comparisons and judge people accordingly? Do you understand the behaviours that your targets cause?

Reblogged this on thinkpurpose and commented:

Why your dog doesn’t like targets and neither should you.

Lovely piece by Squire To The Giants on the variation inherent even in things like walking a dog. I use “how many cups of tea do you drink a day”. Quaint and folksy I like.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Becoming Better and commented:

Thoughtful piece on targets. When are they useful and how do you really make improvements? When is a result a signal and when is it just noise?

Thanks to ThinkPurpose for reblogging so that I could read it and reblog it too.

LikeLike

Brilliant! Great analogy, well written, easy to follow and relate to. Thank you!

LikeLike

No worries Jo. Just trying to explain things, as much for myself as for others 🙂

LikeLike

Nice piece. The world would be a better place if more people understood what you’re writing about here — the idea of common cause variation vs. special cause variation, in particular.

Thanks for linking to my blog, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person